Both my son and daughter play chess. They are 9 and 7, respectively, and they have a 1400 and 900 ELO rating, also respectively. You may not know what an ELO is so the quick definition is that it defines your “level”. Anyone above 2000 is close to a master level. The highest is around 2500. A 100 point difference is enough to predict who is more likely to win. Hence why my kids don’t play with each other!

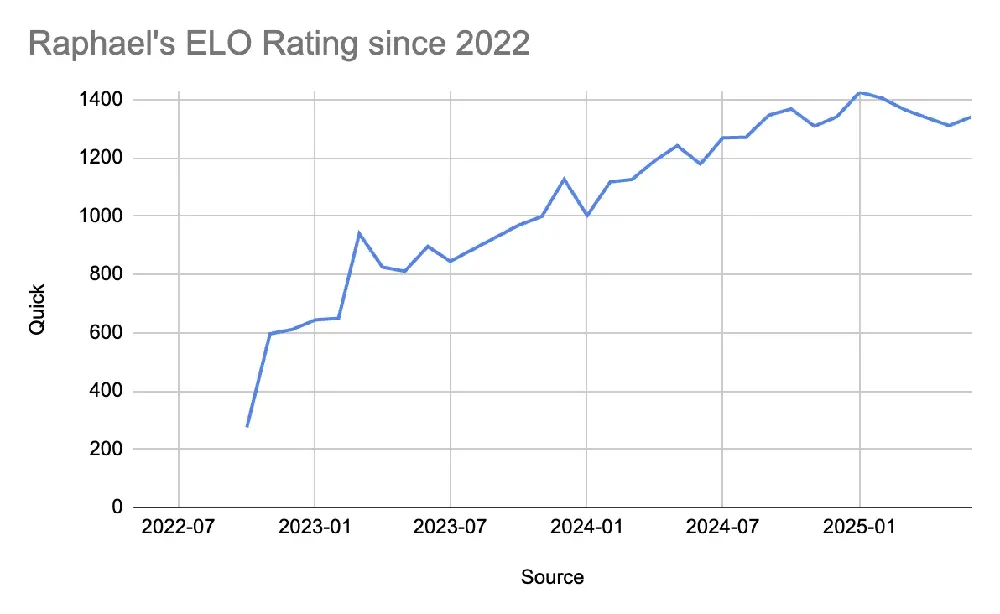

Both my kids started playing when they were 5. They love it! They started with a mere 200 rating and worked their way up. Their rating was never linear as you see in the image below. They get very excited when they win games because their rating goes up, and sometimes even cry after losing a game, mostly because their rating will go down. Hitting a specific target like a 1000 is a milestone or a goal. Their ratings have become their identities!

You may now be guessing why this could be problematic.. Many questions arise: do they play chess for the fun of it or for the rating? Are they just trying to please us? Is it even healthy to compete at an early age?

We don’t really know the answers to all those questions, but one thing we know for sure: we are all learning a lot from the experience.

My wife and I have been doing this for 3 years! We do weekly tournaments, the kids have coaches, we attend national competitions, etc. She is very competitive and I am not. She says they need a push! I say they need space! But we both care immensely about our kids’ wellbeing and future.

So in the process, and probably by accident, we have learned to recognize a few patterns that have helped us find a balance in our different approaches. I decided to share because I see there are parallels here at Meta. We are not officially competing but we could argue that our IC and M+ levels are somehow our identities too.

Without further ado. Here is what I have learned so far:

Lesson 1: You can only compare yourself with who you were yesterday because we are all playing a different game

We know a lot of other chess families. Their kids are also progressing and growing. And sometimes we compare their rate of growth with ours.

My son’s best friend also plays chess. They met in Kindergarten. When we met him, this kid was rated at 400. Today he’s 1700!. He came in 2nd place in the Nationals tournament last Feb. He is awesome! So we ask: How does he do it? What do their parents do differently? What do they feed him??

Unfortunately, when we compare ourselves to others, we feel discouraged, we lose confidence and sometimes we lose enthusiasm. Reacting to these emotions is more likely to take us away from our goals but it’s important to listen to them.

Those feelings are telling us that something needs to change: we can either a) stop playing or change sports, or b) we need to double down and study harder!

But there is a third option that requires reframing our thinking: maybe we shouldn’t be comparing ourselves with others and instead compare ourselves to how we were yesterday.

This happened to me at work. I was comparing myself to other people who got the promotions before I did. I felt discouraged and disappointed. But then later understood that we are all playing a different game. Other people had different childhoods, they grew up in different environments, and they have different genes.

Lesson 2: sometimes you win, sometimes you learn

In chess you only need to win on average 51% of the time to be a Grand Master (and you need to play a lot of games!). That means that even at the top of your game, you will still lose 49% of the time!!

This is one of the biggest lessons IMO: my kids are learning how to lose. Losing sucks!!. Losing makes us feel hopeless, pessimistic, and glum. Reacting to these emotions could take us away from our goals too. These feelings are telling us that something needs to change. We need to reframe our thinking: losing is an opportunity to learn.

This is super relevant to the work we do: some projects fail, some programs pivot, we don’t hit a goal, we don’t get PMF! This is hard and it sucks. There are so many things outside of our control, and since we can only control ourselves, we should focus on learning.

The good news is that our leaders reward such learnings! Learnings can be measured in terms of output such as docs or posts with insights, peer feedback, or even better by starting a new project that addresses all we learned from the failed ones. Fail fast!

Lesson 3: understand the compounding interests of staying in the game

A few months ago I wanted to give up chess. I had good arguments like trying other sports, do more fun stuff, or “let them be kids!”. I had doubts about those questions such as: are they doing it to please us? Are they really getting the benefits of healthy competition? Are we damaging our kids??

But back in Feb, on the plane on our way to Orlando, I met Irina Krush who is the 8 times women’s US champion, ranked #1 chess woman player in the USA. She has a 2500 rating!. We talked for hours and became friends! We started asking her questions about her journey (funny story: her chess.com user name is ikrush, she said it helps a little). One of the most revealing secrets of her success was that she started when she was 7. She became a Grand Master when she was 28 and she never stopped playing and competing. She loves chess (obviously) but she also had to suffer a lot of setbacks to get to where she is.

Maybe the parallels with work on this is that sometimes we change teams, move companies, change jobs altogether. And even though there is nothing wrong with that, especially if you are not enjoying the work (see lesson 4), the people in the highest ranks are usually the ones who have stayed the longest in the same area.

Lesson 4: enjoy the game, winning is just a nice side effect

We keep asking our kids: Do you want to continue playing chess or should we take a break? Are you having fun?? Every time the answer to this question is that they love chess.

I remember when they used to go into a game, we used to tell them: good luck! You will crush your opponent! You are the best! This was problematic because, well, they can’t control luck, their opponents may be stronger, and strictly speaking they are not the “best”. Even saying “I hope you win.“ is problematic because that’s all they will be thinking about.

When playing a game of chess there is only one thing you need to be thinking about: the chess game. Everything else is a distraction.

Thinking about winning, losing, luck or hoping your opponent makes a mistake (also know as Hope chess) is a distraction.

Nowadays, we tell them: have fun and enjoy the game! Don’t worry about winning or losing. You will get an ice cream regardless!

At work, I find myself advising something similar. I say: do not focus on impact, focus on what you want to achieve. What are you passionate about? Are you enjoying the work? This is why hackathons work. It focuses on enjoyment. Impact is just a side effect.