I spent almost two years working hard on the wrong thing because I did not fully understand the problem I was trying to solve. This note is about how I eventually identified the actual problem and how I learned to articulate it more clearly. The first part focuses on the process, the second part on a personal story told in abstract terms. I am sharing this because the insight I learned has changed how I approach work, and I believe it can be useful to others.

Problem Statement

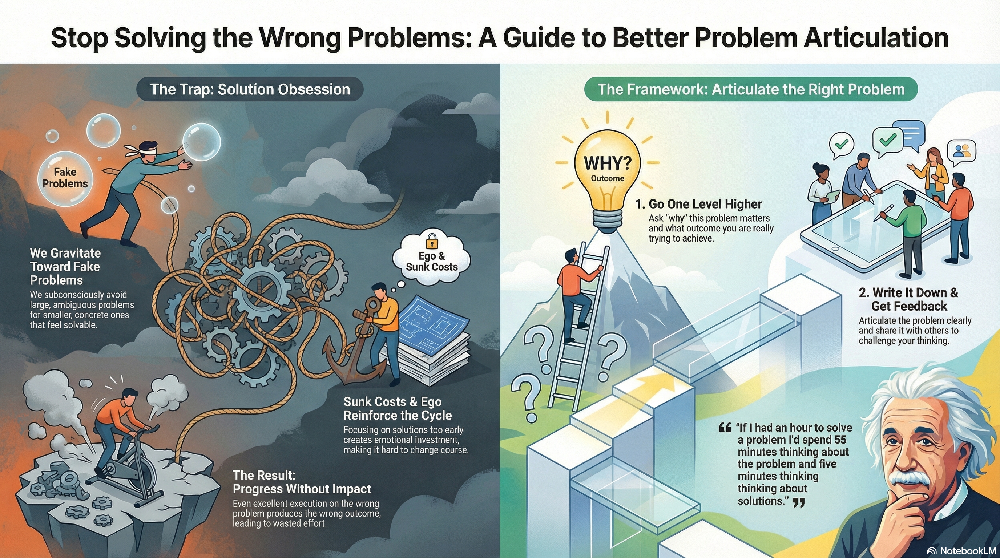

Lack of clarity leads us to focus on the wrong problems. When that happens, even excellent execution produces the wrong outcomes. The real problem is often larger, more structural, and harder to define, so it tends to persist while we treat only its symptoms. When a problem is uncomfortable or ambiguous, we naturally gravitate toward smaller, more concrete problems that feel solvable. This creates progress without impact.

One of the main reasons this happens is that we focus too quickly on solutions. Solutions are appealing: they feel productive, they create momentum, and they give us something to defend. But focusing on solutions too early can obscure our understanding of the problem itself. We become emotionally invested, sunk costs accumulate, and stopping becomes psychologically expensive. Ego and fear of failure reinforce the cycle, sometimes for years.

I believe this is one of the biggest sources of wasted effort at work. When we get problem articulation right, we often achieve outsized impact in a much shorter amount of time.

How Big Is This Problem?

Over a recent twelve-month period, I noticed that I spent only a very small fraction of my time explicitly articulating problems. Most of my time went to discussing solutions, refining them, and executing against them. In hindsight, much of that effort was directionally wrong because the underlying problem was not clearly defined.

I have also noticed that senior people tend to spend more time shaping and reframing problems. One of the defining behaviors of senior roles is the ability to restructure large, ambiguous problem spaces so teams can move faster and have greater impact. This creates some balance in organizations, since senior leaders often define problem spaces. Still, at an individual level, the lack of disciplined problem articulation leads to significant inefficiency.

Proposed Solution(s)

Spend more time articulating the problem. Accept that this is hard and mentally taxing. Write it down. A simple structure that has worked for me is: (1) a problem statement, (2) how big is this problem?, and (3) proposed solution(s). Keep the problem statement short and focused, the size of the opportunity concise, and treat solutions as suggestions rather than commitments. There are usually multiple valid solutions to the same problem.

Ask for feedback early. Share your problem articulation with your manager, a peer, or anyone willing to challenge your thinking. Listen carefully. Check your ego. Say “thank you” and “tell me more.” The goal is not to defend your framing, but to improve it.

Step back and go one level higher. Ask why this problem matters, what outcome you are really trying to achieve, and who benefits if the problem is solved. Consider the end state and work backwards. Use time as a constraint. Break large problems into smaller ones and run experiments to learn more. Aim to communicate the problem so clearly that someone outside your field could understand it.

Broaden your inputs. Reading, listening carefully to others, and reflective practices like journaling, meditation, or exercise can help you notice when your thinking has drifted from problem articulation into solution obsession. This awareness takes practice.

Timebox the process. You rarely get to 100% certainty. There is a real risk of paralysis, especially when information is incomplete or noisy. This is where “done is better than perfect” applies. At some point, you commit, act, and learn.

Finally, life is a balance. Focusing deeply on understanding problems can be slow, intense, and anxiety-inducing. I experienced this firsthand. Solutions are more energizing than problems, and it is okay to acknowledge that. Slow down, pace yourself, and recognize that clarity comes over time.

How Did I Get Here?

For a long time, I believed I was working on an important problem. On the surface, the logic was sound and widely accepted, so I invested heavily in a particular solution. I became attached to it. I defended it. Walking away felt like failure.

The shift happened when someone challenged me with a few simple but uncomfortable questions. Was this solution truly best for the people affected by it, or was it mainly convenient for the system? What was I really trying to achieve by writing and sharing my thoughts? And, most importantly, what did I actually want?

Answering those questions forced me to confront my own motivations. I realized that personal incentives and external validation were subtly shaping how I framed the problem. Once I stripped those away, a different problem emerged. The issue was not the absence of a particular structure or tool, but a more fundamental inability to recognize the same underlying thing across different representations. I had been optimizing a workaround instead of addressing the root cause.

Re-articulating the problem took time and emotional effort. I needed a sounding board. I needed to explain it in simple language. When I could describe it clearly enough that someone with no context immediately understood it, I knew I was closer to the truth.

Key Takeaway

The problem I ultimately want to help solve is not a specific product or system issue, but our collective ability to clearly articulate problems before committing to solutions. When we do this well, we reduce wasted effort and increase impact. I hope more people share notes that focus on defining the problem first, with solutions as a secondary step.

Albert Einstein captured this idea well: “If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.” The quality of the solutions we produce is closely tied to the clarity with which we understand the problem we are trying to solve.